In nearly 20 years of working with boards, we have never seen such public frustration at board performance.

To give a taste of recent headlines, The Economist in December 2024 called out widespread board “fecklessness” in holding management to account, only a few months after academics in the Harvard Business Review criticised their defensive response to emerging technologies. The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer reported an accelerating erosion of trust in business leaders, with a record 68% of respondents believing that businesses purposely mislead people.

The view from the inside isn’t much better. PwC’s 2024 survey of management sentiment towards boards found that only 30% of C-suite executives rated their board as “good” or “excellent”, with 49% wanting at least one of their board directors to be replaced.

Is this frustration justified? And if boards aren’t delivering the impact we expect, why is that? To find out, we combed data from more than 1,000 board members, executives, and governance professionals for clues — and found some unexpected answers.

The shape of the board effectiveness problem

The first signs that there might be room for improvement and that this public concern is well-founded is that directors themselves are raising concerns about board performance.

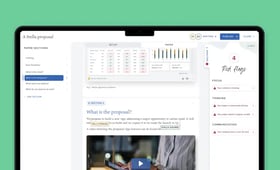

For example, 74% of the directors who have completed Board Intelligence’s Agility Friction Test since 2022 believe their board should spend more time on their organisation’s big-picture vision and goals. And, year-on-year, the proportion of directors who think their board is stuck in the weeds is rising — from 71% in 2022 to 80% in 2024.

This raises an important question: if the big picture thinking isn’t taking place in the boardroom, where it’s supposed to, where exactly is it happening? One could assume that executive teams are picking up the slack, but with only 49% of directors confident they have the quality of thinking they need at every level of their organisation, and executives battling increasingly busy diaries and burnout, this cannot be taken for granted.

Clues can also be found in the topics boards are discussing, the way they spend their time together, and the information they use to understand performance, shape plans, and make decisions.

For example, when it comes to information — one of the board’s most important tools — there is more than a little room for improvement. Our longest-standing piece of research is a joint effort with the Chartered Governance Institute UK & Ireland that helps organisations to assess the strengths and weaknesses of their board packs. Of the more than 1,000 organisations that have used this tool since 2018, 68% have scored their board materials as “weak” or “poor”, while only 1% have rated their board information as “excellent”. It’s also clear that the quality of board packs is worsening: in 2024, only 36% of directors thought their board packs added value, compared with 48% in 2023.

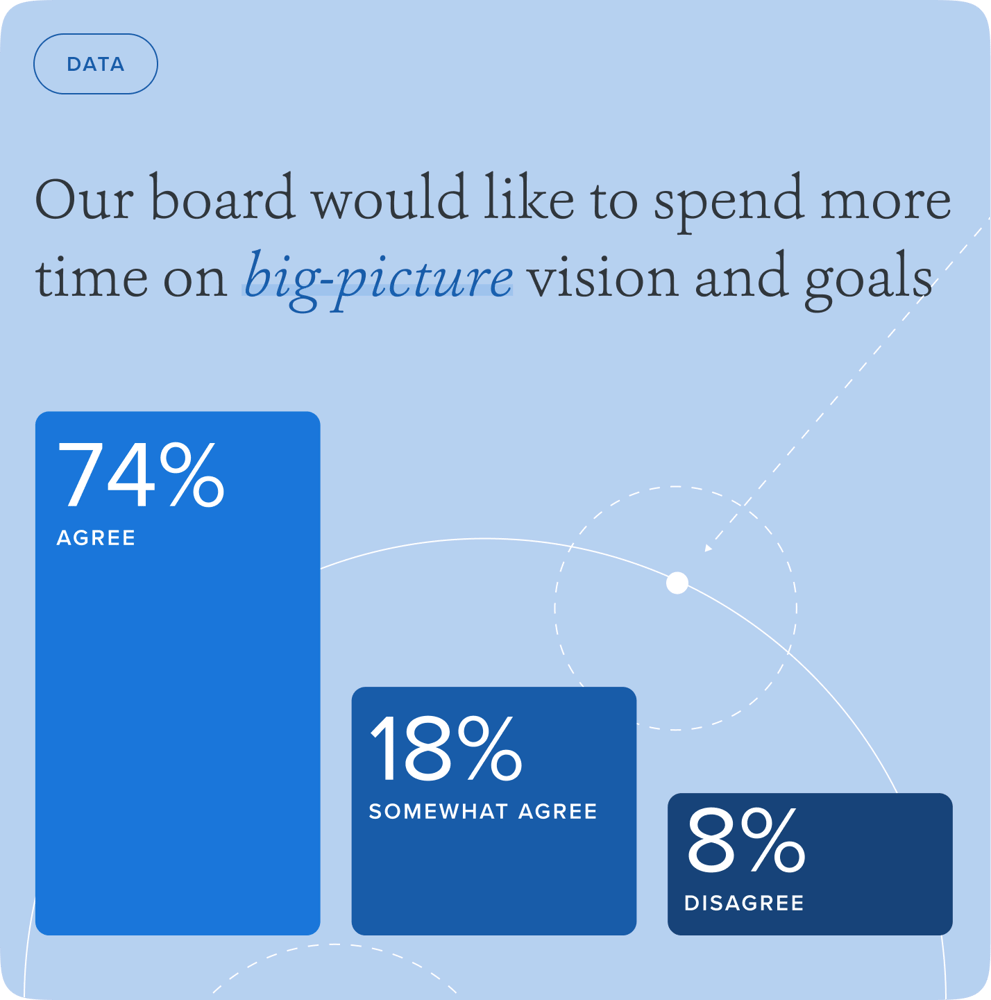

These concerns appear to be impacting the level of confidence with which boards are tackling their organisations’ biggest challenges. In a poll of nearly 300 directors conducted by Board Intelligence in December 2024, 83% said they did not believe their board and management team were set up to harness the opportunities afforded by AI. This is despite widespread acknowledgement that AI will reshape swathes of the economy, and stark warnings from experts that boards and businesses must “adapt [to AI] or perish”.

This may be surprising considering all that boards and governance teams have done to improve board practices and ways of working in recent years. Boards are more diverse than ever, recruitment processes are more rigorous, and an increasing proportion of boards conduct regular external performance reviews, for example.

Against this backdrop, board performance should be improving. And yet, we find ourselves reading headline after headline calling their effectiveness into question — and the statistics do little to challenge the assumption that boards aren’t delivering as they should.

Why is this? Because board composition, recruitment, and assessment were never the only impediments to board effectiveness. Again, our research offers some clues as to what might be getting in the way and shines a spotlight on two performance levers that boards should consider flexing to enhance their value-add.

What are the blockers of board effectiveness?

1. Directors are drowning in information and not sufficiently prepared for board meetings.

Fuel directors with concise, timely, and relevant insight.

The average board meets 8 times a year in full, with a further 5 meetings per committee. The board pack is a vital ingredient in helping these meetings to run smoothly — ensuring directors are fully briefed on the issues at hand and prepared to exercise their steering and supervising responsibilities to a high standard. When boards are composed of predominantly non-executive members, who aren’t working in the business full-time and who often sit on multiple boards and committees at once, it becomes even more important that directors receive timely, accurate, and insightful pre-reads.

“A high-quality performance pack is a really powerful tool that helps the board be much more effective, both as providers for shareholders and as supporters and constructive challengers of the strategy.”

Charles Gurassa, Chair, Channel 4

Despite the important role that board packs play in an effective board, our research suggests that too often they fail to deliver what directors need — being poorly written, badly structured, and over-long. When board packs don’t hit the mark, they not only waste valuable preparation time, but they also make it hard for directors to navigate the discussions and decisions on the agenda with confidence.

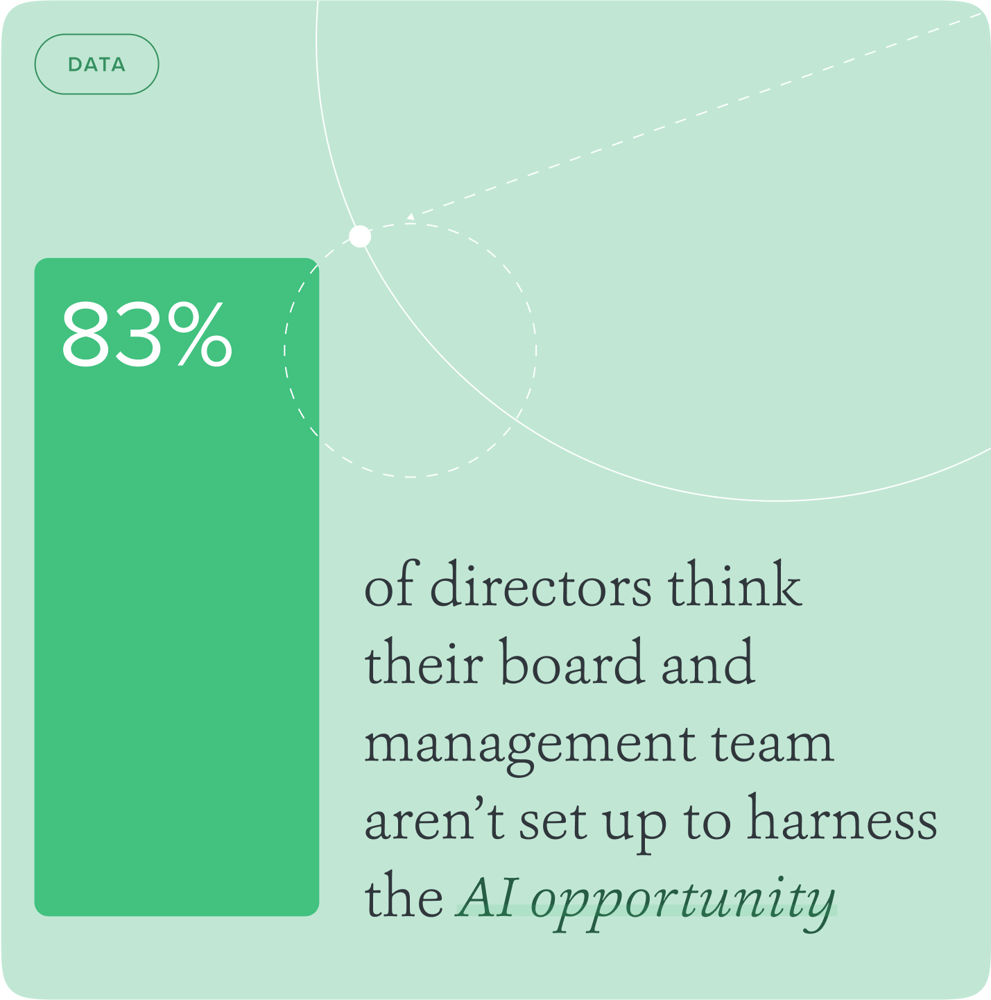

The average board pack for a £500m+ turnover business is now 294 pages long, up from 267 pages in 2023. Add in committee packs, and the directors of the largest companies are now wading through nearly 600 pages of reading material every month.

Directors are smart, but they’re not superhuman. The average director can read up to 30 pages of board pack content per hour, meaning he or she would need to read solidly for two working days every month just to get through the meeting materials — an unrealistic expectation considering directors log between 1.5 and 3.5 days of work per board per month. What’s more, we know from our advisory work that directors spend 3 to 4 hours reading each board pack, which suggests that a lot of pre-reads are too long to reliably get pre-read.

There are also signs that the content itself is increasing the burden on directors — forcing them to read between the lines and dive down rabbit holes for the insight they need. For example, in 2024, 57% of directors said that finding the key messages in their board papers was like looking for a needle in a haystack, up from 50% in 2023. In addition, 42% thought management were not upfront enough about the bad news in their briefing notes.

“It’s incredibly frustrating as a board member when you receive 1,200 pages to read over the weekend and, as a result, you can’t see the wood for the trees. By the time you’ve got through all of that, you realise you’re missing the big picture.”

Sir John Manzoni, Chair, Atomic Weapons Establishment and SSE — read the interview

As if that wasn’t bad enough, 55% told us they receive their board packs under five working days before their board meetings, with 20% rarely or never getting the pack on time. In our research with US corporate directors, 35% expressed frustration at receiving papers too late to adequately review them. Until this improves, time pressure and poor-quality information will continue to interfere with the job boards are trying to do.

It’s true that a roomful of seasoned board directors could very well get to the heart of issues without rigorous pre-read documents, probing for the implications of what they have been told, and sniffing for what they haven’t been told. But it’s hard to expect people who don’t live and breathe a business to be sufficiently attuned to know what questions to ask. And they perform too important a role to simply leave it to chance.

It’s a risk that’s particularly acute when technical issues are concerned. One of the reasons the Post Office continued to falsely prosecute subpostmasters for two decades was that its board lacked the technical literacy to challenge what they were told about the Horizon IT system.

“I wasn’t familiar with the IT language. When discussing IT issues, I didn’t have the same instincts as I had when discussing issues with which I was familiar,” former chair Alice Perkins told the public inquiry into the scandal.

In cases like this one, directors may not even realise that the quality of their discussions is below the standard they would expect, which makes it doubly important that they are able to easily access the thinking that goes behind management plans and proposals.

2. Boards are stretched too thin and not discussing key topics in enough depth.

Plan strategic, forward-looking agendas that make every second of board time count.

The expanding remit of boards is well documented. What’s less commonly discussed — and evident from the research — is how thinly boards are now stretched, and how often their efforts are focused on the wrong things.

Data from our board cost calculators, which help companies to quantify the time and financial burden of board meetings and processes such as minute-writing, shows that the average board meeting for a £100m+ turnover business now lasts 3 hours and 48 minutes and covers 11 agenda items. That means, at best, each item gets only 21 minutes of discussion time. Hardly conducive to sparking creativity, thinking rigorously, or reaching considered conclusions.

Cramped agendas are clearly a problem, given constraints on time. But that problem is made worse when agendas include items that should not be there — and the evidence suggests this is a persistent performance blocker for boards.

Board Intelligence is currently building a range of AI-powered tools to analyse board agendas and meeting minutes, which will shed light on exactly how and where discussion time is allocated. In the meantime, anecdotal evidence from our client work and roundtable events, and directors' feedback on board packs (in which each report corresponds to an agenda item) suggests clear dissatisfaction with the focus of their meetings. For example:

- 66% of the directors we surveyed in 2024 thought that their dashboards and board packs were not a good reflection of their organisation’s priorities.

- 56% said the information they were given was too internally focused.

- 43% of attendees at a recent Board Intelligence webinar said their biggest challenge with board meetings was that they were too backward-looking or operational.

These findings have been reflected in research conducted elsewhere. For example, Korn Ferry found that 37% of S&P 500 directors considered a lack of conversation about strategic direction as one of their top board effectiveness concerns.

All of these issues create barriers to understanding risks and opportunities, which in turn makes it hard for directors to fulfil their legal duties. And there’s a practical performance implication too; when board time is focused on understanding recent operational performance or procedural matters, there’s less space for the forward-looking, strategic discussions and rigorous challenge that directors see as central to their role. It strips attention from the most important items facing the business: the kind that need to be discussed in depth if the board is to add value.

“We would use our time better if we abandoned the ‘high church’ rituals. Wasting the first half an hour reviewing minutes and matters arising does little to set the scene for a rich debate.”

Sir Kenneth Olisa, Chair

What can boards do to improve?

The board blockers suggested by our data speak to a single, underlying problem: boards are not being set up to succeed.

For a long time, the boardroom was the one area of an organisation where the rigour of management science wasn’t fully applied. This was largely because its work was carried out behind closed doors and because boards relied on seasoned, battle-scarred leaders to lean on their sector knowledge and experience to guide the business to success. But with directors becoming younger and more diverse, and with boards grappling with an ever-expanding horizon of complex issues, this is no longer an option.

Although boards today are actively looking to improve their effectiveness, they are still held back by a lack of evidence about the drivers of that effectiveness.

Helpfully, with boards’ increasing use of technology and the emergence of AI tools that can gather and analyse a wide range of datapoints about board performance and operations, directors now have the capacity to put the drivers of their own performance under a microscope, as they would the drivers of organisational performance.

Through forensic analysis of those drivers – whether related to board composition, agenda focus and discipline, meeting structures and behaviours, reporting, or the way directors interact with senior executives — they can deepen their understanding of the science of board effectiveness. And they can act on it, developing bespoke action plans to directly address the issues they surface.

It’s effort well worth investing, because in applying a scientific mindset — and leaning into the methodologies and best practices that have proven successful elsewhere — boards can tap into the marginal gains that they know lead to stand-out performance at any level of a business.

Do boards deliver ROI ?

Boards aren’t cheap to run, and to an extent that’s the way it should be. Their work is too important to scrimp on meetings or to fish for less-experienced non-executive directors.

But where every other part of a business is measured on return on investment, it’s odd that a board should not be — especially considering the average board spends £2.4m per year on writing, compiling, and reading board and committee papers alone. This figure rises to a staggering £7.3m for larger companies (those with more than £500m in annual revenues), which doesn’t include the near £1m investment these organisations make in writing up minutes of their board and committee meetings each year.

Efficiency and effectiveness often walk hand in hand too. Bloated board packs, for example, take longer to prepare and to read, than a more concise and considered version.

Our hypothesis is that by applying scientific rigour to managing its inputs as well as its outputs, boards will raise their ROI even faster.