Our final Think Tank topic of 2019 focused on how boards can take better decisions in steering their organisation; for the good of the organisation and wider society. We were curious about what causes good boards to take bad decisions, and what can be done to reduce the risk of that happening. The insights fall into 4 clusters: improve information, challenge bias, learn from mistakes, and have a clear purpose.

Improve information

“Information is crucial.”

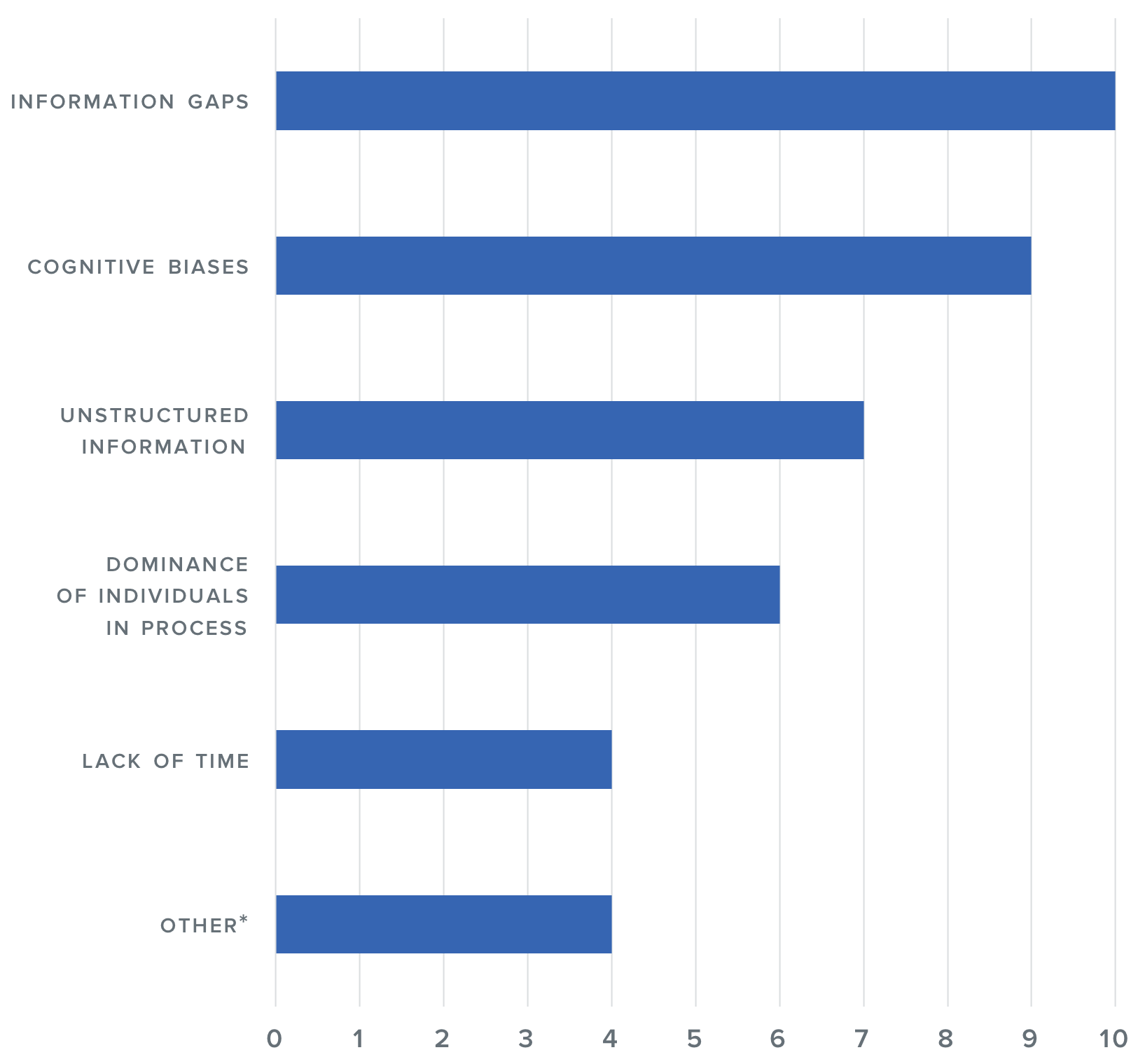

43% of the reasons for poor decisions highlighted were related to information — either poorly-structured or missing:

What are the main drivers of poor decision making in your organisation?

*Other: failure to challenge, organisational issues, pressure, too much detail.

Source: Board Intelligence Think Tank attendees.

The right information, available in good time before a meeting, allows the board to prepare well. Attendees made the following suggestions for preparing for a decision:

- Improve board papers.

There’s no substitute for excellent papers. “Decision papers must detail the options considered and why they were rejected”, “Keep papers short and focus on the key questions relevant to the decision.” - Get out of the boardroom to meet the business.

Boards should spend time with employees to “experience what’s really going on and contextualise their decisions. This helps develop a realistic view of how the company operates and its capabilities.” - Ask questions ahead of time.

Encourage board members to share questions with management in advance of the meeting. “This allows discussion to be more constructive as it allows management time to prepare a response.” - Recognise the limits of your own knowledge.

Don’t be too embarrassed to say you need more time or more information. Challenge the assumptions made. “The hard, or seemingly stupid questions should be asked.” Use sub-groups to get into the detail so board time isn’t diverted. - Delegate as much as possible.

Those who are closest to the business usually have the best knowledge of the impact of the decision. “Decisions made close to the coal face are the best ones.” Whilst not always possible, consulting with those affected improves understanding of the problem and delivery of the solution.

Challenge bias

“I worry about groupthink all the time.”

The second biggest reason given for poor decisions was cognitive bias. Attendees saw this manifesting in three ways: optimism, groupthink and sunk cost.

There were several ‘war stories’ told that illustrated how even the largest businesses and most senior people suffered from these. Several thoughts for improvement were offered:

- Counter management’s natural optimism

and its bigger, scarier sibling “all-consuming obsession”. One way of counterbalancing this is to ask them to present options, explain trade-offs, and to ask them the question “what would happen if we did nothing?”. Another way is differentiating between “fact vs interpretation”when reading a report — challenge management on anything that isn’t fact. - Beware of NED recycling within your industry.

Bringing in “more of the same” can reinforce rather than reduce existing biases and crowd out new ideas that the business needs. “Unchecked, it can lead to repeating rather than challenging past decisions, risking the quality and rigour of the process and outcome.” - Use new NEDs to combat sunk cost bias.

“New NEDs can identify what should be stopped — they can add as much value by stopping unhelpful activity, as by starting it.” - Promote independence of thought and mind.

We need differing perspectives to challenge our decisions and take better ones. “If one person disagrees, then they’re usually right. It should ring alarm bells!” - Explore different perspectives.

Consider getting someone different to chair the meeting, making directors sit in different seats, and including other voices. “We sometimes invite an external expert when making big or difficult decisions, to give a different perspective.” - Consider the long-term consequences.

“Focusing on the significance of quarterly profits for shareholders can skew decisions away from the long-term sustainability of the business and the interests of other stakeholders.”

Learn from mistakes

“As a habit, we don’t learn from our mistakes.”

The final theme discussed by our Chairs was the importance of learning from past decisions to identify what went wrong. Turning this on its head, they also spoke about conducting a ‘pre-mortem’ before you take a decision. Three ideas for learning were brought up:

- Use a pre-mortem to anticipate problems.

Imagine that the decision has ended badly and explore why. These imagined failings allow a deeper understanding of the risks involved and the required mitigations. “We should be pessimistic enough to see what might go wrong and optimistic enough to push through.” - Study mistakes.

“We need to remove the blame culture and make failure acceptable, so that we can learn from our mistakes.” Insights lead to improvements if the learnings are embedded in policies and processes. - Review what went right as well as what went wrong.

Most boards do most things well. In seeking to improve how you make decisions, “don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

Have a clear purpose

Above all of these? A common theme to our Think Tanks this year is emerging: decision making must bear in mind the purpose of the organisation.

“If you don’t know what your purpose is, then you don’t have a hope in getting the decision right.”

We will never know why the Lusitania made the decision to enter military waters, it remains a secret to this day. But you can’t help but wonder about the sequence of events and decisions that lead to the tragedy. Loss of life is thankfully uncommon in corporate life. But poor decision making that leads to corporate disasters can affect thousands of people who lose their jobs, pensions, homes and trust in business.

Pressure from the public and the media spurs Government to lean on regulators to hold companies to account. So, it’s no surprise that regulators are training their red dots on the board and asking for evidence on how they make decisions. We don’t believe that even the best decision process can avoid poor outcomes, but they do make them less likely. A board that can demonstrate their efforts to make better decisions is one that is less likely to be a target for regulators and activist shareholders.