At our most recent Chair Think Tank, we talked about Culture. We had a vigorous debate and share with you some of the emerging thinking below.

In an episode of the 1950s hit sitcom I Love Lucy, Ricky comes home from work and finds Lucy crawling on her hands and knees around the living room floor. Lucy explains that she has lost her earrings. Ricky says “So you lost your earrings in the living room, huh?” She replies “No I lost them in the bedroom but the light in the living room is much better.”

“Where are leaders supposed to look for answers to the culture question? Engagement surveys; turnover rates; diversity metrics; stakeholder feedback; operating profits?”

At the heart of the culture question is a frustration for many Board members: they know it’s important, but don’t know which light on the culture dashboard to pay attention to. And hence, what levers to pull.

But, one thing is plainly obvious; pasting 6 shiny nouns on corporate headquarters does very little to change behaviour. And behaviour is where the rubber hits the cultural road.

Hiding in plain sight

“Organisations have always had cultures: publicly defined or not.” Marcus Aurelius did not define the cultural values of his Roman Empire in 161AD, but moral virtue, self-restraint, mental calm, and civic duty wouldn’t be far from the mark. During the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the cultural norms of the armies, led by the Duke of Wellington and Napoleon respectively, were different. Most obvious was that Wellington was a defensive General and Napoleon an offensive one. Which led to different tactics and attitudes amongst troops. Indeed, American Foreign policy mimics the characteristics of the sitting president.

You can’t stop culture developing, even if you try. Once the cultural die is cast, it is hard to unwind — anyone working for a UK bank can attest to this. Cultural change programmes line the pockets of Consulting firms and keep HR armies busy, but many run out of puff, don’t work, or are undermined by those at the top. One of our guests noted “It is easy for a culture to go from good to bad. It’s much harder to go the other way.”

Culture and values are not going away. Some firms choose to publicly make a big deal of them such as Anthony Jenkins’ RISES movement in 2013. Others prefer to keep shtum. What is unclear is whether or not having a set of stated values which guide employee behaviour actually makes a difference. Lucy Kellaway mocked the values and culture movement in 2015, demonstrating that seventeen of Britain’s 100 biggest companies had no cultural statements; and had financially outperformed the 83 who did.

On the flip side, another attending Chair described in detail the link she observed “between culture, conduct and results in Banking. Particularly on risk committees, the first question they ask is ‘Is this a cultural issue?’” What most people can agree on is: culture exists and when forced to define it, “at bare minimum it makes you think about it; which is a good thing”.

The leader’s shadow

Values are pointless unless the CEO epitomises them; every single day. All the crafting and wordsmithing is undermined the moment the CEO mildly contravenes one value. Local denizens will tut and feel vindicated for their initial cynicism. Or as one Chairman in attendance said with utter conviction “How the CEO behaves overrides all cultural statements”.

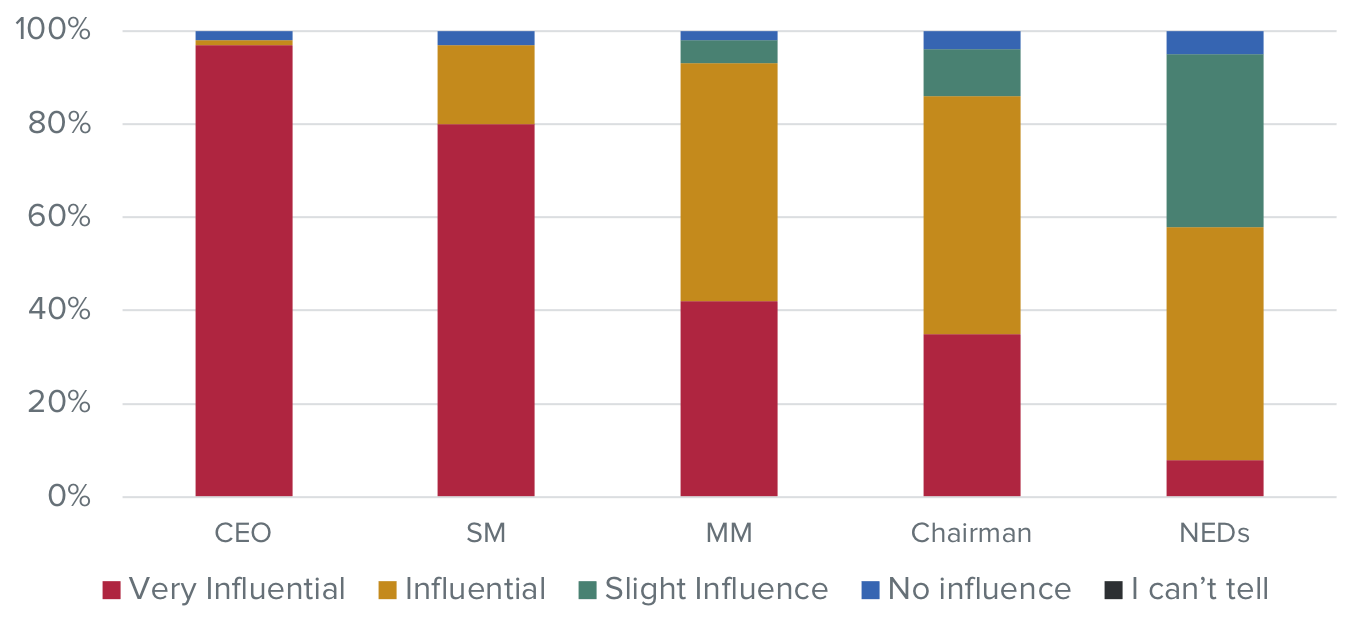

If the behaviour and personality of the CEO is the single biggest influence on culture (see chart), it thrusts recruitment into sharp focus. It was also noted by our Think Tank guests that “the attitude to recruiting a CEO varies considerably between a family-run business and a PLC”.

Family-run businesses tend to have different assessment criteria from PLCs. Front and centre for family-run firms is a version of this question: “Will this individual preserve the culture into the next generation?” Family-run outfits can exercise patience on returns, but rarely gamble with culture.

In contrast, PLCs are much more likely to focus on commercial criteria such as: Can this individual grow shareholder returns? There is a complex tension between these competing priorities. Many PLCs want a good culture but not more than healthy returns. Therefore, they are more vulnerable to falling for the siren call of a narcissist who promises returns, acquisitions or turnarounds. Instead, narcissistic CEOs are positively correlated with overpaying for acquisitions, not outperforming their peers yet commanding higher remuneration. All of which have outsized impacts on how employees feel about the culture they inhabit and the stability of their employment. Culture; conduct; returns.

“Controlling culture means controlling recruitment.” Regardless of the size of the firm, rigorous and impartial assessment of candidates by experts — not just shareholders and Boards — is wise. Once the fox is in the henhouse…

Who’s doing what?

One frustration aired by one of our Chairs was “the lack of published best practice on culture.” Furthermore, firms who have cracked it keep their secrets as a competitive advantage rather than share successes. This may be so, but there is also evidence to the contrary. Below are some examples of different businesses who are performing but have been bold and possibly unconventional in their approach to setting cultural norms:

Paul Polman (retired) from Unilever — listed in London

- First day on the job he scrapped quarterly reporting;

- Unilever’s Sustainable-living plan has ambitious goals to preserve the planets scarce resources;

- He argues that companies are returning too much cash to shareholders via dividends and buy-backs;

- Returns had increased 150% while on his watch, outperforming the FTSE 100. Share price has steadily increased since 2000.

Emmanual Faber of Danone — listed in Paris

- Rejection of the Anglo-Saxon idea that companies exist primarily to maximise shareholder returns;

- On a mission to achieve B-Corp certification. Currently 30% of subsidiaries have achieved it;

- Put his money where his mouth is by selling off profitable businesses that didn’t fit the bill;

- Steady share price growth from 2000.

Garry Ridge of WD40 — listed on Nasdaq

- Evangelist who describes the business as a tribe and employees as tribe members;

- Majors on learning, development, coaching, and caring leadership;

- Rejection of quarterly earnings saying their (Wall St) timelines aren’t the same as his;

- Huge share price growth since 2000.

Sir John Timpson of Timpsons — Privately held

- Popularised upside down management, which shuns rules in favour of trust;

- Actively recruits from the prison population;

- Revenues continue to grow (although data is not public);

- Runs a heavily de-federalised business model with little command and control.

What seems to be common in all cases is that CEOs are adamant about focusing on people and the long term. In some cases they push back against investors (Unilever). While others have patient investors who are on board for the journey such as Coca Cola’s investment in Innocent. This is clearly a selective window of individuals who are not solely responsible for curating a positive culture and supplying decent returns. But all roads do lead to the corner office.

We are seeing more CEOs break ranks with the traditional Friedman view of capitalism. Titan of Wall St Larry Fink was the first. in 2018. Recently followed by fellow titan Jamie Dimon and others. Baroness Dido Harding, who is known for her impassioned leadership style, implores NHS Boards to take culture as seriously as finance. The tide may well be turning in favour of a more culturally sensitive version of capitalism. Only time will tell.

Conclusion

As an expert on Executive selection Robert Hogan notes, “Who you are determines how you lead”. Meaning, if the CEO is a crook or a bully, the cultural values are irrelevant. Values and culture are undoubtedly important and omnipresent. But the moment they are written down or contradicted, they either seem corny or attract cries of hypocrisy.

“The bottom line is: if stakeholders think the culture is rotten they will vote with their feet.”

For Boards, perhaps they don’t need to be crawling around on their hands and knees looking for answers. “But shining a spotlight on recruitment and behaviour seems like a good place to start.”

Further thoughts

What are the dos and don’ts?

It’s a good idea to…

- Bring the voice of the worker into the boardroom;

- Aim for diversity at the top of the organisation, not just the bottom;

- Ramp up the rigour in the hiring of the CEO and recruitment in general;

- Have 3–5 indicators that provide a culture temperature check;

- Assiduously track the reasons for people leaving.

Probably best to avoid…

- Arbitrary common nouns as values or cultural edicts;

- Blind obedience to hard data on culture;

- Hiring a narcissistic CEO (humility is preferable but unfashionable);

- Delegating fluffy cultural stuff to middle managers;

- Perverse incentives.

Whose problem is it?

According to Chairmen and Company Secretaries surveyed, the CEO has the greatest influence on an organisation’s culture

Source: NEDs’ Association, Cultivating Culture Report

Where does it break down?

- 75% of companies define their values but only 6% of companies provide a KPI relating to culture;

- 57% of Chairs talk about culture or values in their Governance Report but only 11% discuss progress in embedding a desired culture.

Source: Black Sun, The Ecosystem of Authenticity, Analysis of FTSE 100 Corporate Reporting Trends in 2019, 14th Edition

Why should we care?

Culture is key to company performance

- 200% higher shareholder returns within organisations deemed to have the healthiest cultures;

- 70% of transformations fail and 70% of those failures are due to culture-related issues.

There is a disconnect between intention and action

- 53% of Chairs feel they should do more on determining their role on culture;

- 48% of Chairs feel there should be greater focus on target culture and tracking progress in achieving it;

- 35% of Company Secretaries observe culture is not considered in boardroom decisions.

Source:

NEDs’ Association, Cultivating Culture Report

McKinsey, Culture: 4 keys to why it matters